|

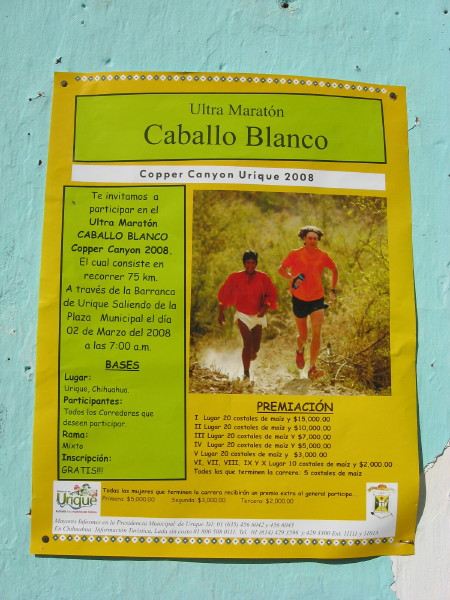

Hueriga!...hueriga! zapuca!! urged the dusky onlookers crowded on the footbridge. Animo!!... apurate!! urged the locals lining the dusty track as they spied their favorites wading out of the Rio Urique. Dozens of runners emerged barefoot with huaraches in hand, or squirting water out of soggy socks and high tech running shoes. They had completed the first fourteen kilometers of the seventy five kilometer Caballo Blanco Ultra Marathon. Some of the Tarahumaran contingent ran in traditional white muslin loincloths with brilliantly colored blouses catching the early morning light. Many carried sticks, possibly since their typical running game involves moving a carved pine-root ball along a fixed course. The sticks help them get the ball out of difficult situations. Often the Indians had extra help from the Virgin de Guadalupe. She adorned hats, and crucifixes, and shirts.

Nearly 150 participants set off in the early morning on the first Sunday in March. Andale!...Look Alive!! We yelled as a strawberry blonde girl ran effortlessly below us. It was a particularly big event for this sleepy mining town. Tourists, reporters, and even the Danza Folklorico from the University of Sinaloa in El Fuerte had all made their way here.

The elite runners from the United States and other parts of the world had only the day before completed their review of the course after the "Club Mas Loco" run from Batopilas to Urique. The route between these two towns in adjoining canyons separated by a hogback range of hills over 4000 feet high serves as the springboard for this grueling endurance race. That was their price of admission, not in dollars or pesos, but in endurance and enthusiasm, and the extraordinary amount of time it takes to get to these remote parts.

|

| Don't Quote Me |

| There's a funny story they tell about the Tarahumaran runners. There was this marathon, which of course is 26+ miles. The Indians sent their representatives. The officials asked why there were only women representing the Tarahumarans. The lead runner replied that since the course was so short, they thought it was a women's race. |

| -Real, or Rumor? |

The winners of the Caballo Blanco Ultra Marathon also win sacks of corn. They get a cash prize, too, but corn is the secret ingredient. Gringo runners would have a world of problems transporting 80 pound sacks of grain up and out of the canyon, onto the train or the plane, etc, etc.; even if they wanted all that corn. Korima is the intrinsic beauty of Caballo Blanco's race. Korima is the Tarahumara word for sharing. It is often used in time of want to lessen the impact of hard times, but at a post race award ceremony it allows all the contestants to share in the victory of the event, not just the individual's achievements. Plus there are prizes for every conceivable catagory: men, women, young, old, fastest, slowest. The Anglo winners who took the stage to accept their prize shared their costales de maize with a local who paced them or inspired them, or donated it to a cause or a family. The proud Tarahumarans are in their finery at the presentation, the women in their voluminous skirts and the men in pleated blouses. Woolen sashes and colorful headbands allow them to distinguish different ranchos. Afterwards, Mexican conjuntos strike up a tune (albeit out of tune), and the party goes on all night.

Our little group of onlookers had taken the easy way to watch the event. We had merely walked from a nearby mesa down to the canyon bottom. Not that our trip was without its measure of endurance, either. This is a mountainous region where mechanized transport is secondary to foot travel. We had taken the Camino Real from the Copper Canyon Train whistle stop at Posada Barrancas on a 3 day, 40 kilometer hike to watch the event. Three days walking to see an eight hour race!! Viva la vida loca!

It turns out that Jilo's roots are in this area. In Churo is a partially restored mission that dates from the return of the Jesuits. Inside the sepulcre in the church courtyard is one of Jilo's relatives, and a founder of Churo. Jesus Mancinas was buried here in 1973 at age 99. Jilo has cousins in the next village, too. It's a real stretch to call the rancho at Chihuirabo a village- it's just an extended family living in 3 or so houses- but Fabian was amenable to our resting there after we met him plowing in his field. Jilo renewed their lineage, and with the sun still up we all went to the house. His wife fed us whatever they had, mostly fresh quelites (garden greens), beans and tortillas, but big portions, and we ate with gusto. After a heavily sugared cup of Nescafe we went for a stroll to his cousins' next door, and practically swooned with excitement at the panoramic view they had of the canyon below. Suddenly a movement far below caught our eye. It turned out to be his cousin Ramon's wife harvesting nopales for an upcoming dinner. She was cutting select prickly pear pads as big as a dinner plate with a machete. Later she would carve out the spines, and then cut the pad into strips. The strips would be soaked in brine, and later mixed with a mole sauce or seared on the comal and served in a fresh corn tortilla. We slept soundly in the tackroom with a blanket on top of sacks of grain.

The next morning we left the mesa country for the canyon bottom. The first step of this spectaclular descent was defined by a rock landing and an elaborate cairn high in the pines. The route started down a bare rock slope, a laja in these parts. It switchbacked relentlessly as we lost elevation. Finally, we heard water. We were still in the pines, but now in a heavily shaded valley. The trail crossed the creek and we stopped to fill our canteens. As the track went around a bend, we were abruptly faced with a totally new environment. Here was another spectacular descent, but this time it was a lush tropical forest. Pochote (kapok), coral bean, pithaya (organ pipe), and agave covered the hills. Our route down was clearly visible, but impossibly steep. Far below was a village. Our trail seemed to end in a broad green boulevard. After adjusting our eyes, it became clear that this was an airstrip long since given over to grazing cows. The village of El Naranjo was in a broad valley of rolling hills, but there was still no river in sight. This was yet a third terrace in the mile high epic vertical drop to the river.

Thankfully, school was in session. Unfortunately, it was completely interrupted by teacher and student alike as we loaded up on soda and cookies at the commisary. Lucky for us we got a well needed caloric infusion and sugar boost after the hot descent, but not so lucky for the schoolkids. They have no choice, and undoubtably little education in matters of nutrition. Maybe that's why cookies in Mexico are fortified with 14 vitamins and minerals. Too bad flouride isn't included, or maybe a prize toothbrush in a bag of Doritos instead of a pog. By now it was midday. Even the normally gnarling curs took no interest in us because of the growing heat. We pushed on for the final three hours of dusty, sweaty hiking on a dusty, twisting, rutted road. Only two vehicles passed. One of those twice, and completely full both times. It was probably the local transport, but they weren't taking on new passengers. We hiked on and kept our eyes on the prize, and the reward was worth it. As we rounded a bend, we saw a long skinny suspension bridge and knew we had made it to the Rio Urique. Bienvenidos a Urique!

After a night to rest up, we were caught up in the fervor on race day, too. We lined the bridge over the track in the morning beside Mestizos and Indians and Anglos. They cheered runners wearing running shorts and tanktops, or loincloths and blouses. The young and old, men and women filled the road. An old Tarahumaran whose bronzed skin looked like a well worn saddle caught my eye. They called him Lechuga, Spanish for lettuce. As the racers passed by, I added my encouragement, "Andale; Animo!"